Notes

German case law understands a threat to a child’s or adolescent’s welfare to be a danger of such a magnitude that, if not addressed, is highly likely to cause considerable damage to the child’s development. If parents are unwilling or unable to avert such existential danger from their children or are even themselves the source of said danger, the state must step in and remove the children or adolescents from the situation (a form of state custodianship).

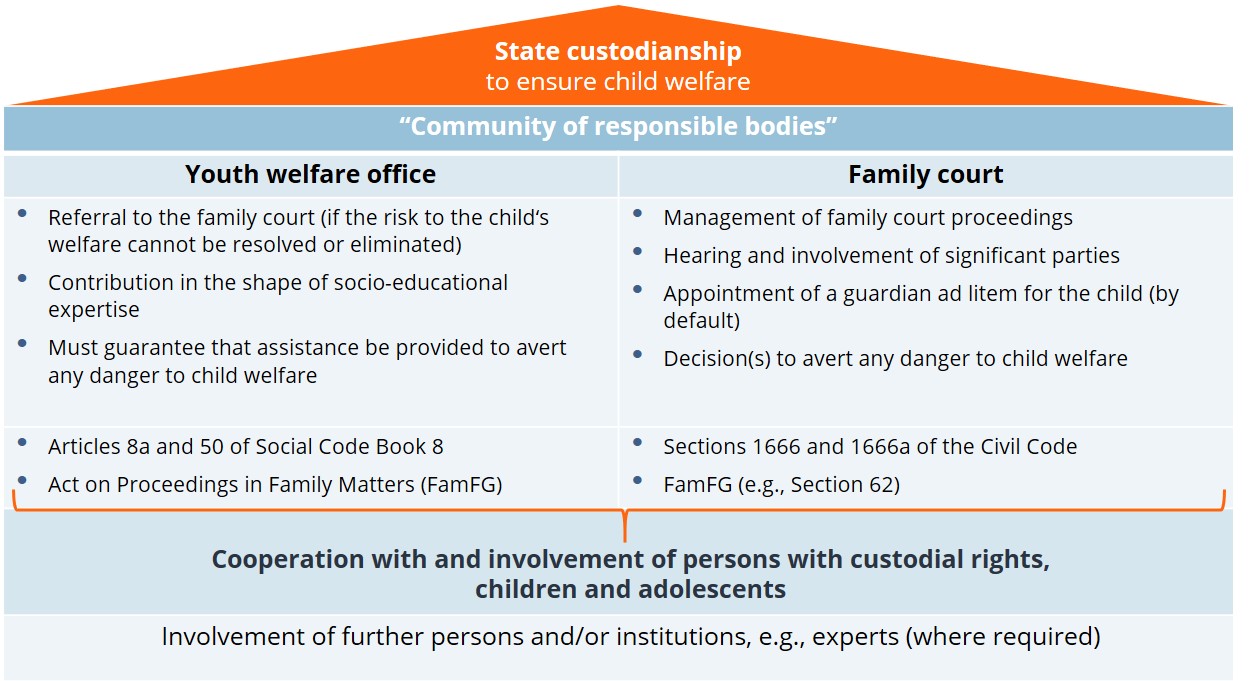

The legal basis for performing this role largely consists of Book 8 of the Social Code (SGB VIII), the family-related provisions of the Civil Code (BGB) and the procedural provisions of the Act on Proceedings in Family Matters and in Matters of Non-contentious Jurisdiction (FamFG). These acts set out the obligation to involve the youth welfare office, as well as the obligation on the part of the youth welfare office to be involved, in family court proceedings.

Section 1666 of the Civil Code (“Court measures in the case of endangerment of the best interests of the child”) specifies the practical implementation of state custodianship. Para. 1 describes the factual preconditions for this, specifically defining how “the physical, mental or psychological best interests of the child” may be endangered, and the willingness and ability of the parents to avert potential danger either by themselves or with assistance. Para. 3 describes the measures the court may take, including instructions, prohibitions, the substitution of declarations of persons with parental custody, or the partial or complete removal of parental custody. Under Section 1666a of the Civil Code, any interventions in parental custody by the family court must be proportionate and may only be exercised after all other forms of support have been provided but failed. Separating children and parents is seen as the last resort.

Role and tasks of the youth welfare office

The youth welfare office, as the executive instance, has specific responsibilities when it comes to averting threats to child welfare (laid out notably in Articles 8a and 50 of Book 8 of the Social Code). Article 50, for instance, requires the youth welfare office to represent the child’s developmental needs sufficiently in family court proceedings. It must also inform the family court of any support services already provided as well as of those yet to come. In most cases the youth welfare office will become aware in the course of its regular duties of any risks to a child’s welfare and will attempt to eliminate these through socio-educational interventions. Should these efforts fail because the parents refuse to allow the risk to the child’s welfare to be assessed, or are unwilling or unable to avert the risk themselves, the youth welfare office will refer the matter to the family court. The intention here is to obtain a court decision concerning, e.g., a partial or complete removal of parental custody rights and the transfer of said rights to a guardian or custodian (see Involvement in family court proceedings in cases of separation/divorce involving parents of underage children) so as to protect the child from any further endangerment to their welfare. Being an administrative body, the youth welfare office is not itself authorised to intervene in parental rights.

Role and tasks of the family court

The family court (as a judicial instance) has sole authority to decide whether the risk to the child or adolescent justifies an intervention in parental autonomy over and above an immediate temporary taking into custody. The family court is the only institution that is legally authorised (by Section 1666 of the Civil Code) to intervene in parental custody rights. In order to establish the basis for such intervention, the court must examine the facts presented along with assessments of the child’s situation (child welfare endangerment), and determine whether the youth welfare office took appropriate action (e.g., through offers of assistance) to avert threats.

In 2022, family courts in Germany intervened in parental custody rights in a total of 28,518 instances:

- 7,464 instructions to seek the assistance of youth support services,

- 4,233 other instructions and prohibitions imposed on guardians (e.g., to ensure that the child attends school, prohibitions on contacting the child, etc.),

- 1,866 supersessions of guardians’ declarations (e.g., on the child’s medical care),

- 7,810 partial transfers of parental care to custodians (e.g., right to determine the place of residence),

- 7,145 full transfers of parental care to guardians.

See also slide 2.6.5.

Procedural law

The Act on Proceedings in Family Matters and in Matters of Non-contentious Jurisdiction (Gesetz über das Verfahren in Familiensachen und in den Angelegenheiten der freiwilligen Gerichtsbarkeit/ Familienverfahrensgesetz, FamFG), which came into force on 1 September 2009, pertains to family court proceedings involving children. It requires matters of this kind to be prioritised and expedited (Section 155), allows for the possibility of an early hearing on child welfare endangerment and for the issuance of an interlocutory order (Section 157) and the appointments of guardians ad litem for children and adolescents to represent their interests in the proceedings (Section 158). Section 163 allows for the submission of an expert opinion.

An important element of a family court proceedings of this kind is the obligation to conduct an in-person hearing with the child or adolescent (Section 159) and persons with parental custody (Section 160).

Further reading

- Balloff, Rainer/Proksch, Roland (2021): Familiengerichtsverfahren, in: Amthor, Ralph-Christian/Goldberg, Brigitta/Hansbauer, Peter/Landes, Benjamin/Wintergerst, Theresia (eds.). In: Wörterbuch Soziale Arbeit. 9th fully revised and updated edition. Weinheim and Basel, p. 287−291.

- Berghaus, Michaela (2020): Erleben und Bewältigen von Verfahren zur Abwendung einer Kindeswohlgefährdung aus Sicht betroffener Eltern. Weinheim.

- Münder, Johannes (eds.) (2017): Kindeswohl zwischen Jugendhilfe und Justiz – zur Entwicklung von Entscheidungsgrundlagen und Verfahren zur Sicherung des Kindeswohls zwischen Jugendämtern und Familiengerichten, Weinheim.

- Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland – Statistisches Bundesamt (2023): Maßnahmen des Familiengerichts bei Kindeswohlgefährdung; GENESIS-Online: Ergebnis 22522-0004 (last accessed: 31 July 2023).