Notes

The Child and Youth Services Act (Kinder- und Jugendhilfegesetz), corresponding to Book 8 of the Social Code (SGB VIII), sets out a broad range of tasks and activities that are (designed to be) coordinated to reflect the integrated nature of child and youth services.

While Book 8 represents a set of socio-educational services that are provided on a case-by-case basis, it also lays out sovereign tasks to be performed in order to protect children and adolescents; specifically, it authorises and requires various forms of intervention [see Fields of work in child and youth services (Articles 11-60, Social Code Book 8)].

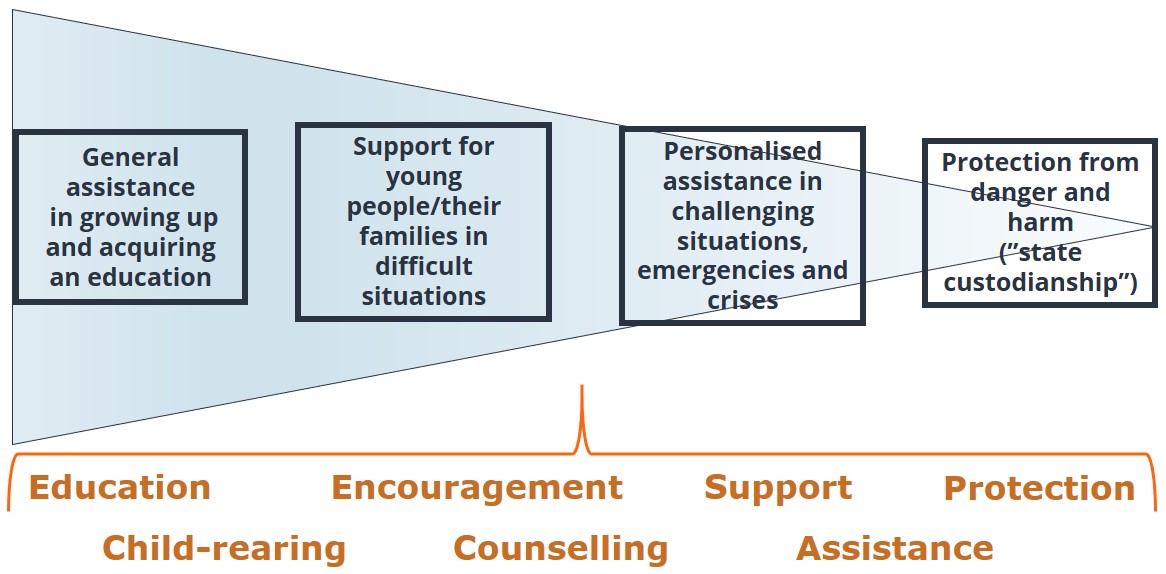

The range of measures and activities reflects the tasks to be fulfilled by child and youth services at several levels.

- First, child and youth services is required to provide young people with general assistance in growing up and acquiring an education. As a rule, the services delivered in this area are targeted at all children, adolescents and young adults and to some extent also to their parents. Examples of these services, which are mostly taken for granted and widely taken up, include child day-care centres and nurseries, youth work, youth education work, and services for parents and families. These are core components of the general child and youth services infrastructure.

- Second, child and youth services provides specific support to individuals in difficult situations. Assistance is provided to parents who wish to separate or divorce, to single parents, and to socially or personally disadvantaged young people who struggle to transition from school to working life, in an attempt to resolve potential problems as soon as they arise. Early intervention (Frühe Hilfen), an interdisciplinary form of assistance offered jointly by child and youth services and the health sector that emerged over the last decade, is part of this field.

- Third, Book 8 of the Social Code stipulates specific support services for children, adolescents and young adults who require them due to

- parents’ lack of ability to raise them,

- personal crisis,

- an inability to participate because of a disability or impairment, or

- lack of maturity (in the case of young adults).

These target groups have a legal claim to these services, the extent of which is beyond the remit of the general support infrastructure, and which require case-by-case planning and intervention. Examples of such services include

- socio-educational support,

- assistance for children and adolescents with a psychological disability, and

- support for young adults.

They can range from non-residential services of differing intensity all the way to the offer of alternative living arrangements for children and adolescents in homes or foster families. - Finally, child and youth services becomes active ex officio when, owing to parents’ inability to do so themselves, it becomes necessary to protect children and adolescents from harm. This is one of the sovereign tasks that are performed by the youth welfare office independently of the wishes of the individuals in question, but not without their involvement. While this can mean action to avert imminent danger (e.g., taking a child into custody), it can also involve participation in contentious family court proceedings or juvenile criminal cases. This reflects the authority of public youth welfare services to execute “state custodianship” (staatliches Wächteramt). These sovereign tasks are designed to help the state fulfil its responsibility for ensuring the care and welfare of children and adolescents.

Given that child and youth services is an integrated entity, experts working in this field must remain mindful of all responsibilities to be met by it as well as of the variety of all tasks and services in its remit. It is not sufficient to limit the focus to their own area of responsibility. Such a blinkered view would run counter to the intention and philosophy behind child and youth services. Regardless of the specifics of their own areas of activity, experts must maintain an awareness of the place they occupy in the system, and cooperate with and make productive use of overlaps with other parts of the child and youth services system.

It follows that all tasks in this area (education, child-raising, counselling, support, assistance and protection) come to bear in all possible contexts, with some given greater weight than others depending on the situation at hand.

Further reading

- Böllert, Karin (ed.) (2018): Kompendium Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. Wiesbaden.

- Hansbauer, Peter/Merchel, Joachim/Schone, Reinhold (2020): Kinder- und Jugendhilfe – Grundlagen, Handlungsfelder, professionelle Anforderungen. Stuttgart.

- Jordan, Erwin/Maykus, Stephan/Stuckstätte, Eva (2015): Kinder- und Jugendhilfe – Einführung in Geschichte und Handlungsfelder, Organisationsformen und gesellschaftliche Problemlagen. 4th revised edition, Weinheim and Munich.

- Münder, Johannes/Meysen, Thomas/Trenczek, Thomas (eds.) (2022): Frankfurter Kommentar SGB VIII Kinder und Jugendhilfe. 9th edition, Baden-Baden.

- Schröer, Wolfgang/Struck, Norbert/Wolff, Mechthild (eds.) (2016): Handbuch Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. 2nd edition, Weinheim and Munich.

- Wiesner, Reinhard/Wapler, Friederike (2022): SGB VIII – Kinder- und Jugendhilfe, Kommentar. 6th edition, Munich.